Article by Massimo Menichinelli (Elisava, Barcelona School of Design and Engineering – UVic-UCC)

Focusing on Communities

Village Hosts represent the meeting of two worlds, urban and rural: whether who run hosting initiative have moved to rural areas from urban ones, or whether they have moved from rural areas to urban areas and then back to rural areas, or because they are hosting guests from urban areas. It is a meeting of two different worlds (but not necessarily that different and far away!), two different types of communities. And increasingly designers and design researchers, formal and informal ones, have been working with communities in an emerging Community-Centered Design approach.

Village Hosts work with communities but could also be considered a community or could be helped in recognizing themselves as part of a community – and this is one of the goals of our work in the OSVH Digital Platform. Platform which, in a community-centered approach, we are developing as open source here: feel free to join the discussion and development about it!

Among the several things to be done when approaching a community, I would like to stress two in this post: getting to know a community and co-designing with it.

How to get to know a community

When working with or within a community, it is always very important first to get to know it – and it’s not always an easy task as it is a living entity! There are also several different types of communities: local communities, communities of practice around a topic, communities around a project, communities around international phenomena… with the OSVH Digital Platform we hope to support all of them, but for now we would like to focus on Village Hosts as a phenomenon, an international community… maybe a movement? This is because platforms work well at (large) scale, so the focus should aim at that (without of course losing the view on the small scale!). We have thus prepared a survey for knowing better all Village Hosts, this will help us to understand them better as a community and how to develop the OSVH Digital Platform for them: please take part in the survey and help us in this!

https://survey.villagehosts.eu/index.php/388974?lang=en

Knowing better who’s part of a grassroot community and what is its nature it is very useful, as bottom-up phenomena never have a formal list, structure, details and data, and it is difficult then to reach and support grassroots social innovators (as we can create new tools, improve the existing ones, promote the community, further develop research and so on). Some years ago, I worked on something similar when studying the Maker Movement with the Maker’s Inquiry approach, and this survey adopts elements and learns from it, so it is based on established work and might also connect communities (several village hosts are makers or even host makerspaces).

How to co-design with a community

If urban/rural village hosts and urban guests are two different worlds, how design could improve the meeting of these two worlds? This can be explored in several ways, and now we focused on: How could Village Hosts co-design initiatives with local rural communities?

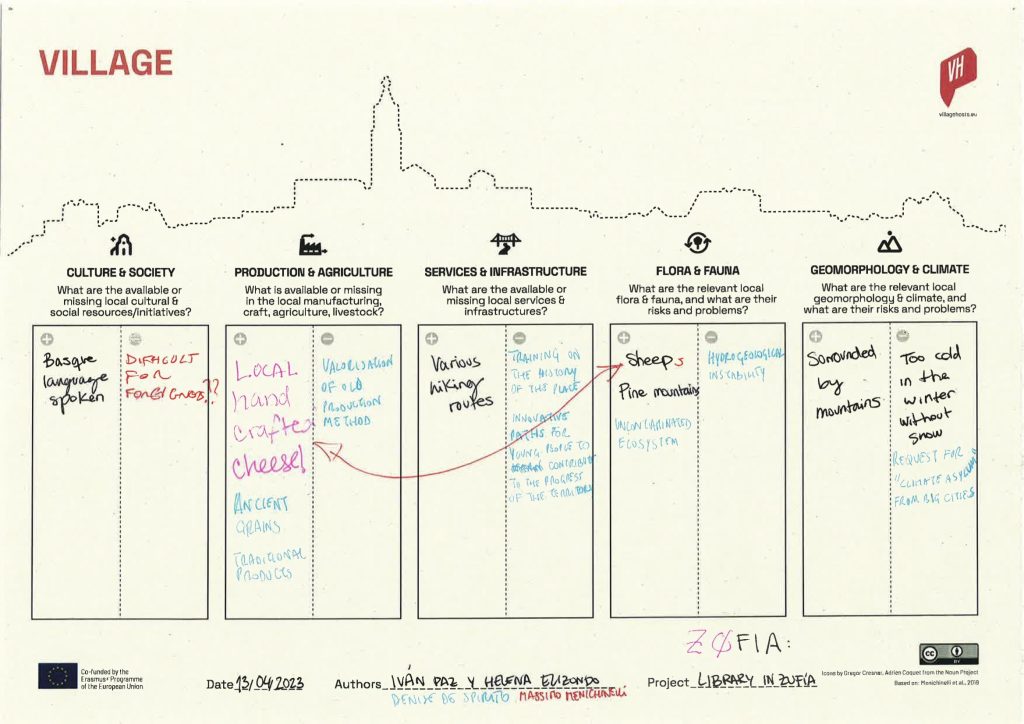

During the Activity 2.2. Co-designing & Co-creation of the Pilot Training from Elisava we presented the OSVH Co-Design Toolbox for Village Hosts, a toolbox for introducing co-design processes in rural areas within social innovation hosting initiatives. It is organized into two parts: in the first part, you can directly co-design a village hosting initiative by focusing on a) the village (its resources, limitations, possibilities) and b) the hosting initiative (its activities, resources, …). Furthermore, the second part adds several more tools for organizing the whole co-design process with all stakeholders, by defining the process with phases that include several activities. The second part was created in order to create a collaboration with all stakeholders of the local community that lasts longer than a workshop, the typical context where such co-design toolboxes are used. With this toolbox thus you can think, discuss and develop a Village Hosting initiative and the collaborative process for defining it. Canvases do not replace an in-depth and detailed design process but are very good for quickly communicating and discussing it with all actors involved.

During the training we used the first version (v1.0, you can dowload it here). The immediate feedback of the participants was positive and suggested improvements (for example, including an example of application), so we took note of their comments and improved it, fixed some errors, added a full example, and now we have a second version available (v1.5, you can download it here)!

Such toolbox was not developed from scratch, but it is based on years of research, for example on my doctoral research about supporting collaborative processes and platforms in the Maker Movement and the Horizon 2020 SISCODE project, to which I participated years ago. SISCODE worked on making Fab Labs, Living Labs and Science Museums as co-creation labs for opening the development of science policies to citizens. Within SISCODE, one of the things I worked at was a toolbox for enabling this, the SISCODE Toolbox for Co-Creation Journeys, and as it was released as open source under a Creative Commons license, we further extended it and adopted it to the context of Village Hosts with the OSVH Co-Design Toolbox for Village Hosts. Both share the same approach: reusing and integrating existing tools and providing long lasting toolboxes that further advance how design can work collaboratively with communities.

Co-funded by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union

Co-funded by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union